Optimal information and support on new patient diagnosis of multiple sclerosis

MS MasterClass 2, 2018

‘Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an acquired chronic immune‑mediated inflammatory condition of the central nervous system (CNS), affecting both the brain and spinal cord. It affects approximately 100,000 people in the UK. It is the commonest cause of serious physical disability in adults of working age.

People with MS typically develop symptoms in their late 20s, experiencing visual and sensory disturbances, limb weakness, gait problems, and bladder and bowel symptoms. They may initially have partial recovery, but over time develop progressive disability. The most common pattern of disease is relapsing–remitting MS (RRMS) where periods of stability (remission) are followed by episodes when there are exacerbations of symptoms (relapses). About 85 out of 100 people with MS have RRMS at onset. Around two‑thirds of people who start with RRMS may develop secondary progressive MS: this occurs when there is a gradual accumulation of disability unrelated to relapses, which become less frequent or stop completely. Also about 10 to 15 out of 100 people with MS have primary progressive MS where symptoms gradually develop and worsen over time from the start, without ever experiencing relapses and remissions.

The cause of MS is unknown. It is believed that an abnormal immune response to environmental triggers in people who are genetically predisposed results in immune‑mediated acute, and then chronic, inflammation. The initial phase of inflammation is followed by a phase of progressive degeneration of the affected cells in the nervous system. MS is a potentially highly disabling disorder with considerable personal, social and economic consequences. People with MS live for many years after diagnosis with significant impact on their ability to work, as well as an adverse and often highly debilitating effect on their quality of life and that of their families.’ 1

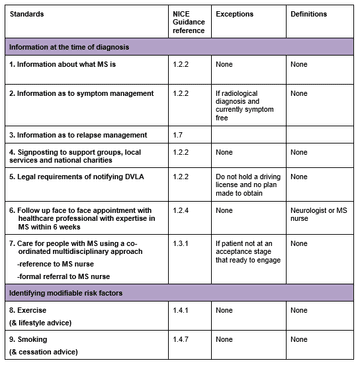

The core recommendations laid out by NICE CG186 for the management of multiple sclerosis are detailed below. These recommendations of care pertaining to the information and support at time of diagnosis of multiple sclerosis and ascertainment of generic modifiable risks are the subject of this audit which attempts to ascertain whether the non-specialist general neurologist is meeting these in their district general practise (Princess Alexandra Hospital).

Core recommendation of NICE CG186 on management of diagnosis of MS:

1.2 Providing information and support

1.2.1 NICE has produced guidance on the components of good patient experience in adult NHS services. This includes recommendations on communication, information and coordination of care. Follow the recommendations in Patient experience in adult NHS services (NICE clinical guideline 138).

Information at the time of diagnosis

1.2.2 The consultant neurologist should ensure that people with MS and, with their agreement their family members or carers, are offered oral and written information at the time of diagnosis. This should include, but not be limited to, information about:

- what MS is

- treatments, including disease‑modifying therapies

- symptom management

- how support groups, local services, social services and national charities are organised and how to get in touch with them

- legal requirements such as notifying the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency (DVLA) and legal rights including social care, employment rights and benefits.

1.2.3 Discuss with the person with MS and their family members or carers whether they have social care needs and if so refer them to social services for assessment. Ensure the needs of children of people with MS are addressed.

1.2.4 Offer the person with MS a face‑to‑face follow‑up appointment with a healthcare professional with expertise in MS to take place within six weeks of diagnosis.

Ongoing information and support

1.2.5 Review information, support and social care needs regularly. Continue to offer information and support to people with MS or their family members or carers even if this has been declined previously.

1.2.6 Ensure people with MS and their family members or carers have a management plan that includes who to contact if their symptoms change significantly.

1.2.7 Explain to people with MS that the possible causes of symptom changes include:

- another illness such as an infection

- further relapse

- change of disease status (for example progression).

1.2.8 Talk to people with MS and their family members or carers about the possibility that the condition might lead to cognitive problems.

1.2.9 When appropriate, explain to the person with MS (and their family members or carers if the person wishes) about advance care planning and power of attorney.

1.4 Modifiable risk factors for relapse or progression of MS

Exercise

1.4.1 Encourage people with MS to exercise. Advise them that regular exercise may have beneficial effects on their MS and does not have any harmful effects on their MS.

Vaccinations

1.4.2 Be aware that live vaccinations may be contraindicated in people with MS who are being treated with disease‑modifying therapies.

1.4.3 Discuss with the person with MS:

- the possible benefits of flu vaccination and

- the possible risk of relapse after flu vaccination if they have relapsing–remitting MS.

1.4.4 Offer flu vaccinations to people with MS in accordance with national guidelines, which recommend an individualised approach according to the person’s needs[3].

Pregnancy

1.4.5 Explain to women of childbearing age with MS that:

- relapse rates may reduce during pregnancy and may increase three to six months after childbirth before returning to pre‑pregnancy rates

- pregnancy does not increase the risk of progression of disease.

1.4.6 If a person with MS is thinking about pregnancy, give them the opportunity to talk with a healthcare professional with knowledge of MS about:

- fertility

- the risk of the child developing MS

- use of vitamin D before conception and during pregnancy

- medication use in pregnancy

- pain relief during delivery (including epidurals)

- care of the child

- breastfeeding.

Smoking

1.4.7 Advise people with MS not to smoke and explain that it may increase the progression of disability. (See Smoking cessation services NICE public health guideline 10.)

Objectives

To determine if NICE clinical guidance (CG186) for the management of multiple sclerosis in adults and the key priorities for implementation regarding information and support at time of diagnosis is acknowledged and adhered to by the non-specialist general neurologist in the district general hospital of Princess Alexandra Hospital district general.

Sample

Small cohort with new diagnosis of relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis reviewed in an 18 month period in 2015-2017 2013 in general neurology outpatients or as acute admissions.

Exclusions

- New diagnosis consultation not on the electronic platform.

- Co-morbid learning disabilities or other communication difficulties.

Method

- Create a database of new relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis patient diagnoses seen in the general non-specialist neurology outpatients between 2015 and 2017.

- Obtain electronic record of consultations of the selected RRMS and assess whether standards detailed below and as per NICE CG 150 are recognised and met by the secondary care provider –using the initial assessment of the consultant neurologist recorded in the clinic notes and letter.

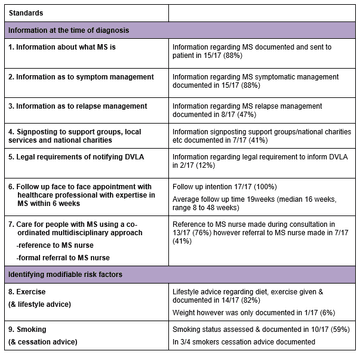

Standards

To gain insight into the patients given a new diagnoses of RRMS (their epidemiological profile and topography of disease at presentation).

To ensure that the core recognised standards of best clinical practise particularly with reference to information and support provided as set out in the NICE clinical guidance CG 186 are met in >70% of cases:

Results

Only 17 new diagnoses of RRMS with sufficient electronic access identified for evaluation (unfortunately no outpatient coding by disease is performed to easily access the population and cases were obtained from those consultants who continue to process all clinic letters through word with search of ‘multiple sclerosis’, ‘RRMS’, ‘MS’ or ‘clinically isolated syndrome’/’CIS’). Although the cohort largely reflected one consultant practise, at least three different consultant assessors were reviewed.

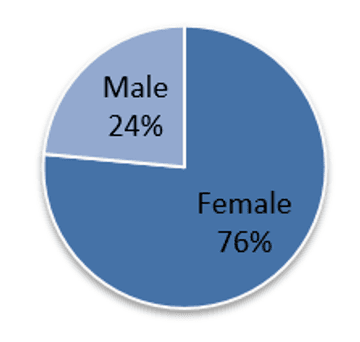

The patient cohort (n17):

Average age: 42 years and 3 months (median 40 years and 6 months, range 16 to 73)

Symptom duration at time of review: 10 weeks (median 7 weeks, range <1 week to 24 weeks)

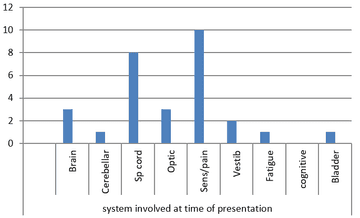

Anatomical system involved at time of presentation:

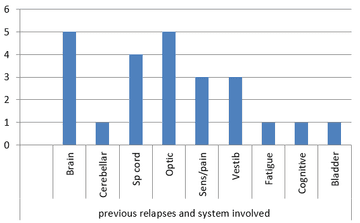

Average prior probable relapse episodes: 1.7 (median 1 episode, range 0 to 6 episodes)

Anatomical system involved in relapses prior to diagnosis:

Time from first encounter to formative test: 1.6 weeks (median <0 weeks, range 0 to 4 weeks)

Time from test to follow up feedback: 3 weeks (median 0 weeks, range 0 to 20 weeks)

MR neuroimaging available at time of first encounter in 10/17 (59%)

Of the tests arranged during patient journey:

- MRI with gad in 17/17 (100%)

- Bloods in 15/17 (88%)

- LP in 10/17 (59%)

- VEP’s in 8/17 (47%)

- Serial imaging within 18 months 15/17 (88%)

When specific standards interrogated:

Conclusions

The observations of this audit are made on the written communication and available electronic clinical notes and this does not necessarily reflect all that is communicated with the patient and failure to achieve standards cannot be translated to poor care but simply what is documented.

The caveat is that this is a very small population which is biased to patients where diagnosis was transparent and as such a more rapid diagnostic turnaround possible. It is also noted that the majority (59%) presented with scans already available which may reflect more acute pathology with imaging expedited prior to review.

It is noted

- Spinal cord and sensory disturbance were the most frequent symptoms at presentation in this cohort.

- Symptoms had typically been present for several weeks (median seven weeks).

- Past history of probable relapses were evident in the majority with a median of one previous episode often allowing a high index of clinical suspicion at the time of first encounter. The most common relapses pertained to brain, optic nerve, spinal cord, sensory and vestibular dysfunction.

- Patients once seen had investigations initiated rapidly at <2 weeks and all patients ultimately had MRI with GAD with the majority also getting serial scanning arranged in the following 18 months (88%). LP and VEP’s were not always pursued when clinical presentation and imaging were felt sufficient, with additional tests arranged in no more than 59%.

Consultant assessors in addressing the reviewed standards:

- Provided and documented good patient education with information on MS and support regarding symptomatic management in the vast majority (88%). There was also evidence of a holistic approach with consideration of modifiable risk factors including lifestyle and exercise (in the majority 82%).

- Follow-up was arranged in 100% of patients however the standard of offering a six week contact was not met in 100% of patients as at present we have no capacity to do this with over 600 patients across four consultants already breached on their follow up and limited MS nurse support. Follow-up was arranged at a median of 16 weeks and I suspect this reflects consultants arranging appointments in a time frame that they hope will be met.

- Patients are not being steered to support groups/charities and although reference is made to the MS nurse in the majority (>70%) only a minority are referred immediately following consultation. I suspect from my own practice that this often relates to how ready the patient is to engage with these other sources of support and when a more rapid diagnosis is made additional bedding in time is often given before then bringing this to the table. Re-assessment of this in follow up would be interesting.

- Similarly plans for relapse management are not as frequently documented as symptomatic management (47% v 88%) and this again may be down to deferring this to when patient has accepted their condition.

- One clear failing is that patients are not being advised that they have a legal obligation to inform the DVLA and this needs to be resolved.

Recommendations

- System of outpatient coding or database required to enable effective audit – personally achieved through individual practice database

- There is disparity in the documented information and signposting/referral to resources and this may be best addressed by a standard text or leaflet that is encouraged to be used across consultants – I have amended mine to also reference the wisdom of smoking cessation in smokers and the legal obligation to inform the DVLA which were not at present addressed in the template

- To consider ring fencing a follow-up appointment on each consultant list on a monthly basis to ensure more rapid face-to-face follow-up of this and other critical patients. Alternatively (and a more ideal solution) recruit a hospital-based MS nurse who can absorb this as one of her roles thereby also ensuring that patients have access to the nurse support and practical help and guidance – currently business case for MS nurse in progress.

References

Refer to NICE CG186: Multiple sclerosis in adults: management

More MS Academy Diagnosis & assessment Projects

Encouraging excellence, developing leaders, inspiring change

MS Academy was established five years ago and in that time has accomplished a huge amount. The six different levels of specialist MS training are dedicated to case-based learning and practical application of cutting edge research. Home to national programme Raising the Bar and the fantastic workstream content it is producing, this is an exciting Academy to belong to.